Dry January: an opportunity to rethink alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption is a pressing public health issue in Europe that is responsible for nearly 800,000 deaths annually in the WHO European Region. A significant proportion of these deaths is due to non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular diseases (40%) and cancer (15%). With profound health, social, and economic consequences, alcohol contributes to over 200 diseases, including seven types of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and liver-related illnesses.

Europe also has the highest alcohol consumption levels in the world. On average, adults consume 9.2 litres of pure alcohol per year, driving a direct correlation between alcohol consumption and liver mortality in 21 out of 28 EU Member States. The economic toll is immense: in 2018, alcohol-attributable cancers alone cost the European Union nearly EUR 5 billion, accounting for 10% of the total cost of cancer deaths in the region.

Contrary to popular belief, no level of alcohol consumption is safe—even low or moderate levels carry long-term health risks. Initiatives like Dry January are an opportunity to raise awareness, encourage healthier habits, and reduce the immense burden alcohol places on individuals and society.

“800,000 annual alcohol attributable deaths in Europe!! 40% cardiovascular, 15% cancer and 13% liver cirrhosis. “European Alcohol health Alliance”, let’s reduce alcohol-related harm together!”, Aleksander Krag, EASL Secretary-General, on X (11 December 2024)

What is Dry January?

Dry January is a global public health campaign that encourages people to abstain from alcohol throughout January. Launched in 2013 by the British organisation Alcohol Change UK, it has since gained international popularity. Many take this alcohol-free month as an opportunity to reset their drinking habits, improve their health, and assess their relationship with alcohol.

“There’s a crisis and emergency around alcohol consumption. To reduce harm, we need to turn off the tap. Prohibition is unlikely, but at least we can ring-fence an element of road safety with respect to consumption. Alcohol is the most common cause of advanced liver disease and death.”, Prof. Frank Murray, EASL Policy, Public Health and Advocacy Committee Member, in an article from Euractiv (22 December 2024)

How alcohol damages the liver

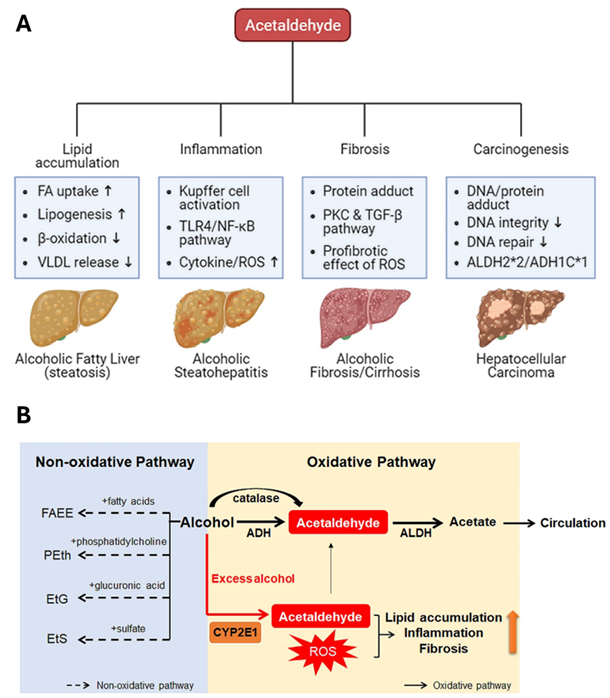

The liver plays a central role in processing alcohol, but excessive drinking can lead to severe and progressive damage. The breakdown of alcohol produces acetaldehyde, a harmful byproduct of alcohol metabolism that accumulates in liver cells. This accumulation can lead to fat buildup (steatosis), inflammation (hepatitis), and eventually scarring (fibrosis). Over time, this damage can progress to cirrhosis, an irreversible state which significantly increases the risk of liver failure or cancer (Figure 1A).

Additionally, oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage further exacerbate liver cell injury. Although damage occurs in stages, early intervention and sustained abstinence can halt progression and even allow for partial recovery in early stages of liver disease.

In the liver, alcohol is metabolised through oxidative and non-oxidative pathways (Figure 1B). The oxidative pathway, primary mechanism of alcohol breakdown, involves enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1), and catalase, which convert alcohol into acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde is then further broken down into acetate and eventually excreted from the liver. During excessive alcohol consumption, CYP2E1 becomes more active, leading to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

The non-oxidative pathway, responsible for a smaller portion of alcohol metabolism, involves enzymes that conjugate alcohol with endogenous metabolites, forming byproducts like fatty acid ethyl ester (FAEE), phosphatidylethanol (PEth), ethyl glucuronide (EtG), and ethyl sulfate (EtS). These byproducts, along with acetaldehyde and ROS, greatly contribute to liver damage by promoting lipid accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis. Acetaldehyde is recognised as a toxic compound, while ROS generated by CYP2E1 activation are major contributors to liver injury. Additionally, acetate and non-oxidative metabolites are also implicated in liver damage.

Assessing alcohol consumption in liver disease management

Determining a patient’s alcohol consumption remains a significant challenge in liver disease management. The World Health Organization introduced in 2001 the the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), a simple method for identifying excessive drinking and for assisting in a quick assessment. While self-reports can aid in prognostication, they are often imprecise due to intentional and unintentional underreporting. Biomarkers such as PEth show potential for improving accuracy, but gaps in understanding its metabolism persist, limiting its clinical application.

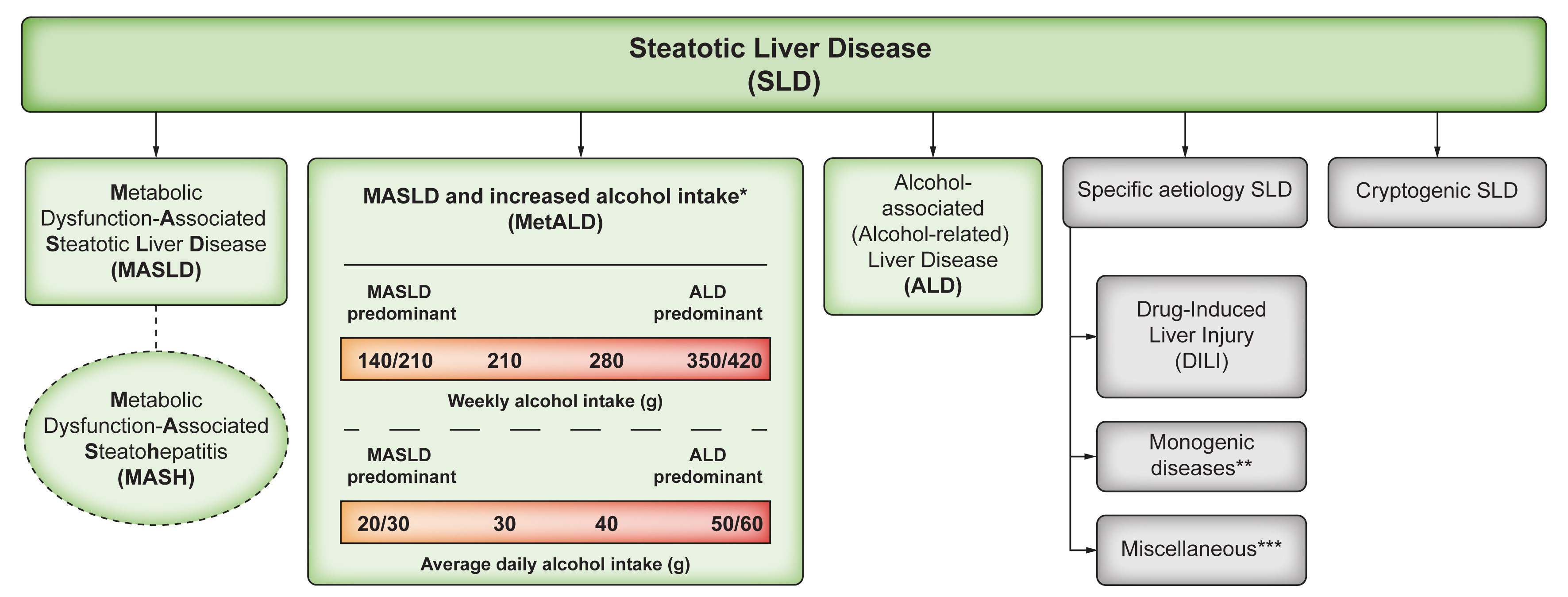

The adoption of the new nomenclature of steatotic liver diseases (SLD) in 2023 offers a fresh perspective, reducing the stigma associated with the term "nonalcoholic" in NAFLD, making the condition more inclusive and less judgmental. It also enhances clarity and understanding for both healthcare providers and patients, offering a more comprehensive framework for addressing liver conditions linked to metabolic dysfunction.

SLD is a broad category with multiple causes, including metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), and their overlap metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-related liver disease (MetALD). Other aetiologies of SLD, such as genetic or viral factors, are managed separately, and advancements in understanding disease mechanisms may lead to further refinement of diagnostic categories, including cryptogenic cases and coexistence with other liver diseases.

Moreover, the new nomenclature emphasises the synergistic relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiometabolic risks, encourages enhanced screening for alcohol use, unlocks new research opportunities, and facilitates easier recruitment for clinical trials, thus paving the way for groundbreaking advancements. For more insights into this topic, explore EASL Studio S7E7: "Alcohol, Cardiometabolic Risk Factors, and Steatotic Liver Disease – From Stigma to Breakthrough Therapies". The episode is available as a video or podcast.

To support healthcare professionals in addressing alcohol-related liver diseases, EASL provides evidence-based recommendations and tools for clinical practice. EASL has published two important Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) that provide valuable guidance for managing patients with alcohol-related liver disease and related conditions:

• EASL Clinical Practical Guidelines: Management of Alcoholic Liver Disease 2012.

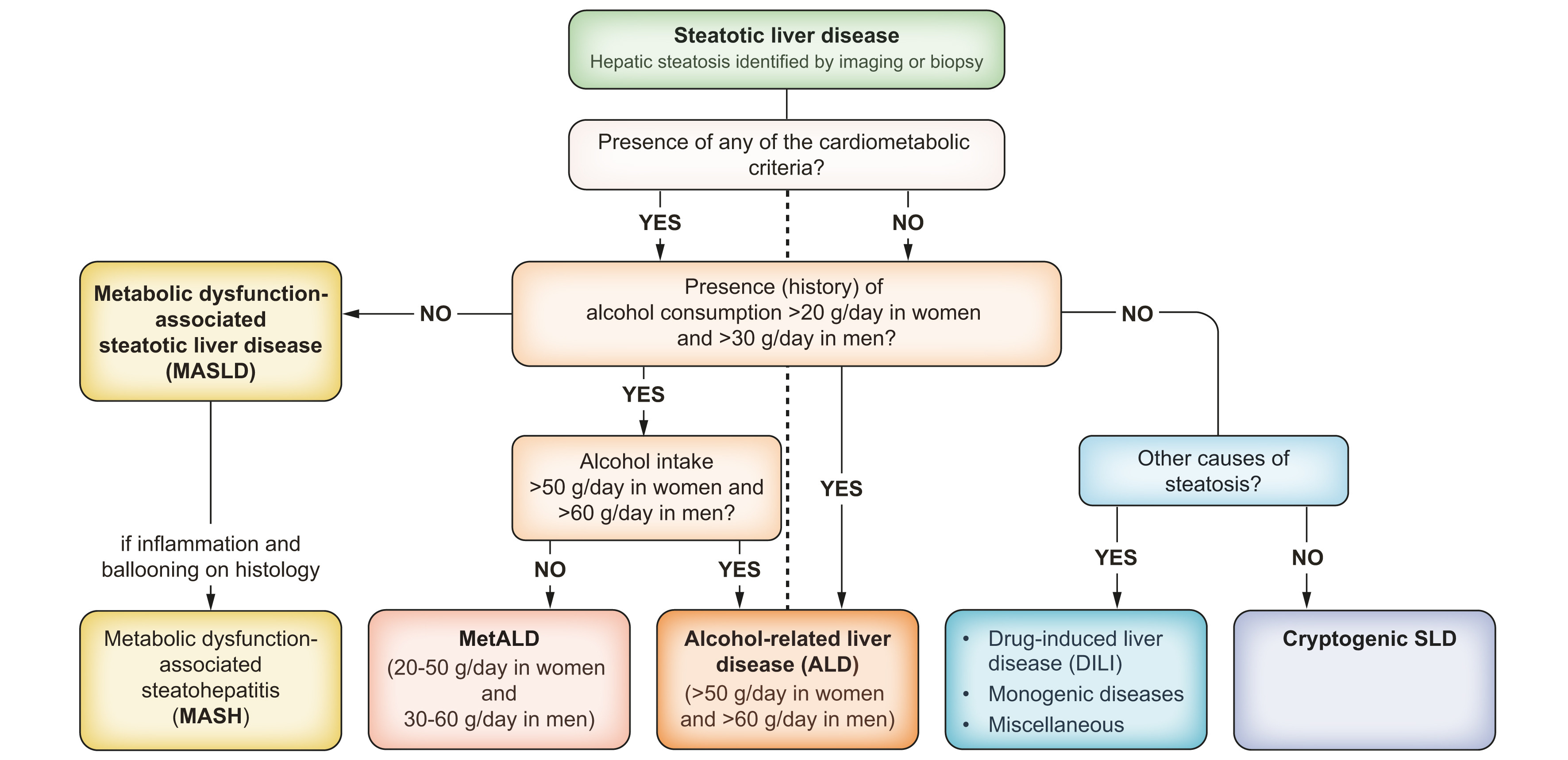

The 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines define steatotic liver disease as encompassing various causes, with alcohol consumption and other factors assessed using medical history, psychometric tools, or biomarkers. Alcohol intake above 20 g/day in women and 30 g/day in men is key in diagnosing SLD. Moderate alcohol consumption (20–50 g/day in women and 30–60 g/day in men) is indicative of MetALD, a combination of MASLD and alcohol influence. Higher alcohol intake (>50 g/day in women and >60 g/day in men) indicates ALD (Figure 3).

If you are eager to learn more, check out the position statement entitled “Metabolic Dysfunction and Alcohol-related Liver Disease (MetALD): Position statement by an expert panel on alcohol-related liver disease” in JHEP.

Alcohol’s impact of health and well-being

Alcohol impacts nearly all aspects of life. It is a leading cause of liver diseases such as cirrhosis and fatty liver. It also contributes to mental health conditions, cardiovascular problems, and addiction. In addition, excessive alcohol consumption may impair relationships, reduce productivity, and increase the risk of accidents. Initiatives like Dry January, offer a chance to take a break from alcohol, reset habits, and assess these effects. Even a short-term break from alcohol can improve both short-term well-being and long-term health.

“A growing proportion of younger people are being treated for liver disease and liver failure.”, Debbie Shawcross, EASL Vice-Secretary, in an article from BBC (25 November 2024)

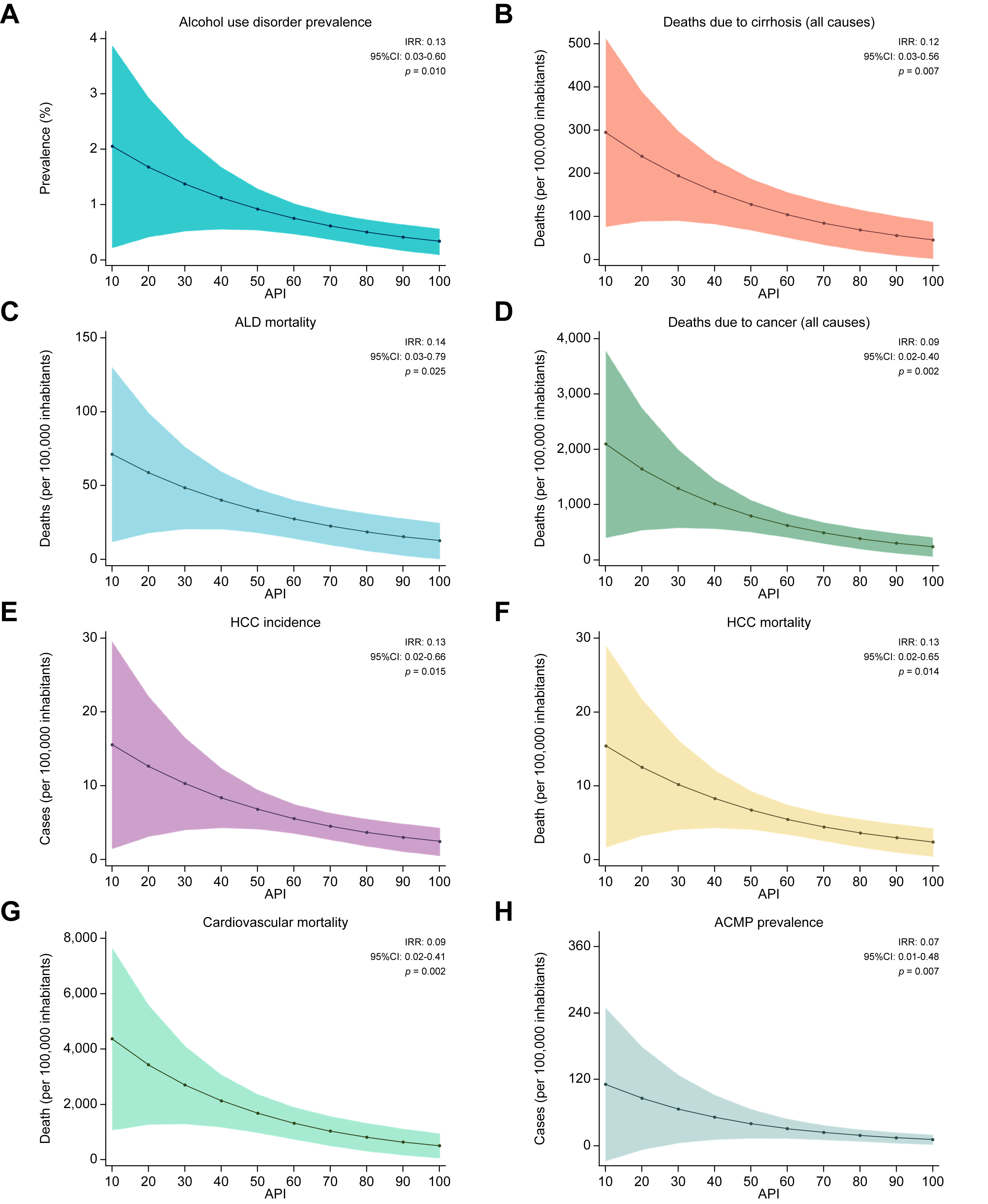

In a recent paper, Díaz and colleagues suggest a new tool, the Alcohol Preparedness Index (API), to evaluate the strength of alcohol-related public health policies across countries. A more stringent policy environment is linked to reductions in alcohol use disorder (AUD) prevalence and alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) mortality over time. Strengthening alcohol-related policies may also reduce long-term mortality from cardiovascular diseases, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and other cancers. The study shows that countries with higher API scores experienced lower AUD prevalence and lower mortality rates related to ALD, neoplasms, HCC, and cardiovascular diseases (Figure 4).

Over time, the association between a higher API and improved health outcomes became stronger, suggesting that the development and enforcement of alcohol-related public policies can significantly reduce alcohol-related disease burden.

Another recent document, “Alcohol and Cancer Risk: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory” highlights the strong link between alcohol consumption and an increased risk of at least seven types of cancer (liver, breast, oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, oesophagus, and colorectal cancers). Here, alcohol is identified as the third leading preventable cause of cancer in the United States, contributing to approximately 100,000 new cancer cases and 20,000 cancer-related deaths each year. The advisory also points out that less than half of Americans are aware of this connection, emphasising the need for better public education. To address this, it recommends updating alcohol labels to include cancer warnings like those on tobacco products. This initiative is part of global efforts to raise awareness of alcohol's dangers and encourage informed decision-making about alcohol consumption.

EASL’s commitment to public health and alcohol harm reduction

“1 in 11 deaths in Europe are caused by alcohol, they are 100% preventable. Policies informed by scientific evidence are more likely to address health challenges effectively, reducing disease burden and improving population health outcomes.”, Aleksander Krag, EASL Secretary General, during the WHO European Alcohol Health Alliance Symposium (11 December 2024)

EASL plays a key role in raising public health awareness about the harmful effects of alcohol, actively contributing to the global conversation with its policy statements and research. To reduce the impact of alcohol-related liver diseases and promote prevention, EASL has published three policy statements:

• EASL Policy Statement: Reducing Alcohol Harms 2023;

• Reducing the burden of Alcohol Related Liver Disease (ARLD) 2019.

These publications reflect EASL’s ongoing commitment to addressing the challenges of alcohol-related liver disease and its impact on public health. The policies not only call for improved prevention and treatment strategies but also stress the importance of integrating alcohol-related liver disease management into broader public health initiatives. To explore this topic further, read the paper “Public health policies and alcohol-related liver disease” in JHEP Reports and watch the latest EASL Policy Dialogue “Current Initiatives and Developments in Alcohol Policies in Europe”.

Make your impact

“Some of the patients that I look after do Dry January and then on 1 February they go out on a big binge. This is really harmful, because suddenly you’re drinking excessively, causing harm to your liver and undoing all the good of not drinking in January. So while it’s wonderful to give your liver a rest for a month, it is overall a lot better to be drinking sensibly throughout the year than to do things in extremes.”, Debbie Shawcross, EASL Vice-Secretary, in an article from The Guardian (3 January 2025)

Learn more about alcohol's impact on your health and how Dry January can benefit you and others by exploring the links below!

Resources

• EASL Studio S7E7: “Alcohol, cardiometabolic risks factors, and steatotic liver disease – From stigma to breakthrough therapies”.

• EASL Studio S5E9: “Alcohol and the new nomenclature – A game-changer?”.

• EASL Studio live from EASL Congress 2023: “The battle to reduce alcohol harms… EASL’s new policy”.

• EASL Studio S4E8: "Alcohol and food policies".

• EASL Studio S4E3: “A 360 approach to beat alcohol-related liver disease”.

• EASL Studio S3E5: “JHEP Live: Stigma and alcohol”.

• EASL Policy Dialogues S3E8: “Current Initiatives and Developments in Alcohol Policies in Europe”.

• EASL Policy Dialogues S2E9: “Preventing liver disease with policy measures: The Hepahealth II study”.

• EASL Policy Dialogues S2E8: “The political battle to reduce harms caused by alcohol”.

• EASL Policy Dialogues S1E2: “The liver, alcohol, and politics”.

• NAFLD Summit 2022 session “Nutrition/food, alcohol and environmental toxins as (co-) factors of NAFLD”.

• EASL Journal Club: “Prognostic performance of 7 biomarkers compared to liver biopsy in early alcohol-related liver disease”.

• EASL Quiz questions related to “Metabolism, alcohol and toxicity” to test your guidelines knowledge.

• Online course: “Prognostic performance of 7 biomarkers compared to liver biopsy in early alcohol-related liver disease”.

• Online course: “Post Graduate Course 2021: Lifestyle and the Liver”.

Events

• Do not miss the EASL SLD Summit 2025 sessions entitled:

“Understanding the combined role of alcohol and cardiometabolic risk factors”,

“Interactions between alcohol and metabolic risk factors" and

• In May 2025, join the EASL Congress 2025 sessions:

“European Alcohol Health Alliance” and

“EASL/SALVE Symposium: Controversies in the management of patients with alcohol use disorder”.

Make it your New Year resolution to join us in Amsterdam or online on 7-10 May 2025. Early fee registration ends on 14 January!

Articles and references

• Empowering public health advocates to navigate alcohol policy challenges: alcohol policy playbook, World Health Organization, 2024.

• European framework for action on alcohol, 2022–2025, World Health Organization, 2022.

• Dry January challenge, Alcohol Change UK.

• Alcohol is a public health challenge. Why don’t we see it that way?, Mariam Zaidi, Euractiv, 2024.

• I had no idea being a social drinker would damage my liver by 31, Hazel Martin, BBC, 2024.

• Love your liver! 19 simple ways to look after this incredible organ, chosen by doctors, Sarah Phillips, The Guardian, 2025.

• Alcohol and Cancer Risk: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory, 2025.

• Factsheet – 5 facts about alcohol and cancer, World Health Organization, 2021.

• Hyun J et al. Pathophysiological Aspects of Alcohol Metabolism in the Liver. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 May 27;22(11):5717. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115717.

• Kronsten et al. Adolescent sobriety under siege - an urgent call to protect children from alcohol harms. J Hepatol. 2024 Dec 9:S0168-8278(24)02764-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2024.12.010.

• Musto et al. Is there a safe limit for consumption of alcohol? J Hepatol. 2024 Nov 1:S0168-8278(24)02645-X. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2024.10.024.

• Rinella ME et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023 Dec 1;78(6):1966-1986. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000520. Epub 2023 Jun 24.

• Arab JP et al. Metabolic Dysfunction and Alcohol-related Liver Disease (MetALD): Position statement by an expert panel on alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2024 Nov 26:S0168-8278(24)02728-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2024.11.028.

• Díaz LA et al. Association between public health policies on alcohol and worldwide cancer, liver disease and cardiovascular disease outcomes. J Hepatol. 2024 Mar;80(3):409-418. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.11.006. Epub 2023 Nov 21.

• Ventura-Cots M et al. Public health policies and alcohol-related liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2019 Aug 8;1(5):403-413. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.07.009.

• Lee BP et al. Designing clinical trials to address alcohol use and alcohol-associated liver disease: an expert panel Consensus Statement. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep;21(9):626-645. doi: 10.1038/s41575-024-00936-x. Epub 2024 Jun 7.

• Danpanichkul P et al. Global and regional burden of alcohol-associated liver disease and alcohol use disorder in the elderly. JHEP Rep. 2024 Jan 26;6(4):101020. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101020.

• Avitabile E et al. Liver fibrosis screening increases alcohol abstinence. JHEP Rep. 2024 Jul 2;6(10):101165. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101165.

• Habash NW et al. Epigenetics of alcohol-related liver diseases. JHEP Rep. 2022 Mar 10;4(5):100466. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2022.100466.